Which Aluminum Alloys Work Well with ER4943 Welding Wire

- 1 What is Aluminum Welding Wire ER4943?

- 2 Understanding Aluminum Alloy Classification Systems

- 3 Chemical Composition Requirements for ER4943 Compatibility

- 4 The 6xxx Series: Primary Application Territory for ER4943

- 5 Can ER4943 Join 5xxx Series Aluminum Alloys?

- 6 Working with 3xxx Series Alloys and ER4943

- 7 Pure Aluminum and 1xxx Series Compatibility

- 8 Why 2xxx and 7xxx Series Require Different Approaches

- 9 Dissimilar Alloy Combinations with Aluminum Welding Wire ER4943

- 10 Cast Aluminum Alloys and Application of ER4943 Filler

- 11 Impact of Temper Condition on Welding Behavior

- 12 How should dissimilar alloy combinations be handled with ER4943?

- 12.1 The 6xxx series is the primary application territory for ER4943 — why is that the case?

- 12.2 Can ER4943 join 5xxx series alloys?

- 12.3 Why do 3xxx series alloys accept a variety of fillers?

- 12.4 When is ER4943 acceptable for pure aluminum and 1xxx series materials?

- 12.5 Why do 2xxx and 7xxx series alloys require specialized approaches?

- 13 Corrosion Resistance in Various Alloy Combinations

- 14 Color Matching and Anodizing Considerations

- 15 Industry-Specific Alloy Selection Guidelines

- 16 Troubleshooting Incompatible Alloy Combinations

- 17 Practical Selection Process for Real-World Applications

- 18 Future Trends in Aluminum Alloy Development

In modern aluminum fabrication, choosing the right filler material often determines whether a welded structure performs as intended over time. Aluminum Welding Wire ER4943 is widely discussed because it sits at the intersection of chemistry, weldability, and practical fabrication needs, especially when multiple alloy families are involved. As manufacturers face increasing pressure to balance durability, appearance, and production efficiency, understanding how this welding wire interacts with different aluminum series becomes a foundational skill rather than a specialized niche. From common structural alloys to architectural extrusions and mixed-material assemblies, ER4943 frequently appears in real-world decisions where material behavior in the weld zone matters as much as design calculations on paper.

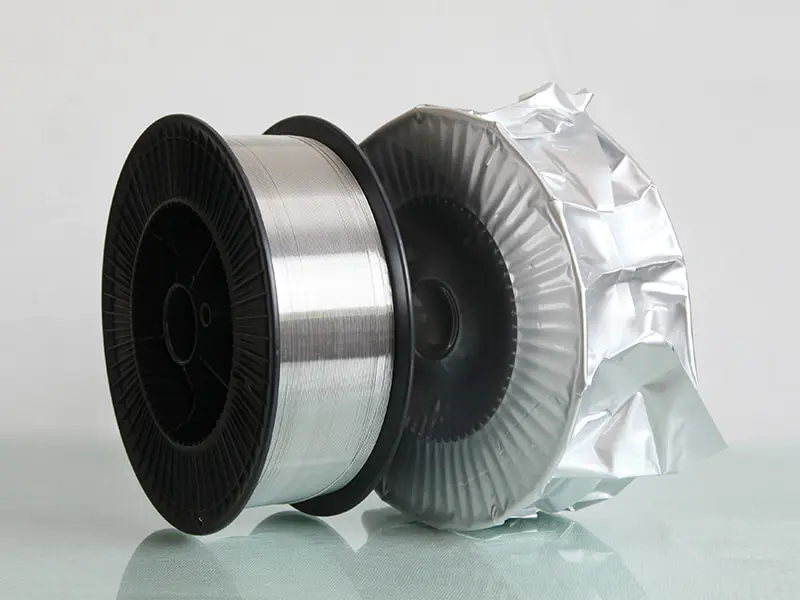

What is Aluminum Welding Wire ER4943?

Aluminum Welding Wire ER4943 is a solid aluminum filler wire developed for joining aluminum components where stable weld formation, controlled fluidity, and balanced mechanical behavior are required. It is used during fusion welding to supply molten metal that bridges two aluminum parts, becoming an integral part of the joint after cooling. Rather than acting as a coating or surface aid, ER4943 becomes part of the final structure, influencing how the welded area responds to load, temperature changes, and environmental exposure.

Understanding Aluminum Alloy Classification Systems

Aluminum alloys are identified through a four-digit numbering system that highlights their main alloying elements and general traits. This setup groups materials into series based on primary additions, allowing similar properties within each group. Welders and fabricators familiar with this system can reason about weldability and filler match even for new alloys in a known series.

The wrought aluminum designation system identifies series using an initial digit, with each series corresponding to a primary alloying element. This structure lets engineers and shop workers grasp core material features quickly without recalling every detail. The second digit shows changes to the base alloy or tighter impurity controls, and the last two digits pinpoint the exact alloy in the series or purity level for some groups.

A key split lies between heat-treatable and non-heat-treatable alloys. Heat-treatable types build strength via solution treatment and aging, forming tiny particles that block metal movement. Non-heat-treatable ones gain strength from work hardening or solution effects. This difference affects welding greatly: heat-treatable materials soften in zones near the weld from heat, while non-heat-treatable ones keep more uniform traits across the joint.

Temper labels after the alloy number describe the heat or work history that set the current state. An annealed version of an alloy welds differently from the same alloy in a hardened temper, influencing crack risk and final joint behavior. Welders consider both alloy series and temper when picking fillers and planning procedures.

| Series | Primary Alloying Element | Heat Treatable | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1xxx | Pure Aluminum | No | Electrical conductors, chemical equipment |

| 2xxx | Copper | Yes | Aerospace structures, high-strength needs |

| 3xxx | Manganese | No | Cooking utensils, architectural, general fabrication |

| 4xxx | Silicon | Varies | Filler metals, brazing sheet, castings |

| 5xxx | Magnesium | No | Marine, automotive, pressure vessels |

| 6xxx | Magnesium + Silicon | Yes | Extrusions, automotive, architectural |

| 7xxx | Zinc | Yes | Aerospace, high-strength applications |

The relationship between base metal chemistry and filler selection stems from what happens when materials mix in the weld pool. Dilution—the percentage of base metal melted and incorporated into the weld—alters filler metal composition toward base metal composition. A filler metal that resists cracking in undiluted form might become crack-susceptible when mixed with certain base materials. Understanding this interaction allows fabricators to predict outcomes rather than discover problems after welding.

Chemical Composition Requirements for ER4943 Compatibility

Aluminum Welding Wire ER4943 features silicon and magnesium added in defined ranges that play a central role in determining which base materials will mix well to form reliable weld metal after dilution takes place. The silicon level enhances fluidity in the molten pool and tightens the temperature span during solidification, lowering the likelihood of hot cracking. Magnesium supplies additional strength and helps shape the grain pattern in the weld.

When ER4943 combines with base metals that have similar elements in matching amounts, the finished weld retains good crack resistance and suitable mechanical traits for practical use.

Base materials with high copper content cause difficulties when paired with ER4943. Copper sharply raises hot cracking risk by forming low-melting layers at grain boundaries as the weld cools. These layers create fragile routes where cracks can begin and travel. Even modest copper levels can change a crack-resistant filler into a troublesome one once copper enters the weld chemistry through dilution, turning a stable combination into one prone to defects.

Zinc brings parallel challenges, encouraging hot cracking as the metal solidifies and potential stress corrosion cracking in service under specific conditions. Base materials carrying notable zinc usually need different fillers rather than ER4943. Zinc also heightens porosity chances due to its low boiling point, releasing gas that forms bubbles in the weld.

The final proportions of silicon and magnesium in the weld metal shape many key traits. Excessive silicon without sufficient magnesium can result in joints with reduced strength, even if cracking is controlled. Too much magnesium compared to silicon boosts strength but increases cracking vulnerability. ER4943 aims for an even starting point, though base metal contribution alters this.

Suitable base materials hold silicon and magnesium in amounts that preserve workable balances after blending, ensuring the weld behaves predictably.

Predicting the final chemistry of the weld metal relies on a clear grasp of dilution rates, which vary depending on the welding process, specific parameters, joint design, and technique used. Typical dilution percentages give fabricators a practical tool to assess whether a particular base material and filler combination will produce workable alloy makeup. Joints with shallow penetration incorporate less base metal into the weld pool, while those with deeper reach draw in more, altering the resulting mixture and its properties.

Understanding these interactions helps in selecting pairings that yield consistent outcomes without hidden flaws. It also guides the development of welding procedures that factor in how much base material enters the pool, making sure the joint achieves the desired crack resistance and strength levels.

Paying close attention to element boundaries avoids unforeseen reactions, letting ER4943 function as designed on suitable materials. This focus on chemistry details leads to welds that perform reliably in challenging uses, steering clear of frequent issues from poorly matched pairings.

Fabricators who monitor dilution effects and conduct small test welds build assurance for full-scale production, lowering wasted material and repeat work while improving overall efficiency and quality.

In practice, dilution acts as the link between filler and base, blending their chemistries in proportions set by heat input and penetration depth. Higher heat or deeper joints pull more base into the mix, shifting the balance toward the parent material. Lower settings keep the weld closer to the filler's original composition.

Recognizing these tendencies allows adjustments in settings or filler choice to hit the target alloy range. Small-scale trials—often simple mock-ups—offer a low-risk way to check predictions. These tests show actual dilution under shop conditions, confirming if the weld metal stays within safe limits for cracking and strength. Results inform procedure changes, ensuring larger runs proceed with fewer surprises.

Tracking dilution patterns over multiple jobs creates valuable shop knowledge. Records of settings, joint types, and outcomes reveal trends, making future selections quicker and more accurate. This gathered insight turns chemistry management into a repeatable advantage, supporting steady production and fewer costly fixes.

Metallurgical compatibility is not limited to avoiding cracks; it also includes achieving sufficient strength, maintaining corrosion resistance, and creating joints that perform reliably throughout their service life. To achieve a truly compatible combination, multiple factors must be satisfied simultaneously.

The 6xxx Series: Primary Application Territory for ER4943

Heat-treatable aluminum alloys in the 6xxx series represent the natural application territory for Aluminum Welding Wire ER4943. These materials contain both magnesium and silicon as primary alloying elements, creating base metal chemistry that dilutes favorably with ER4943's composition. The resulting weld metal maintains crack resistance while providing adequate strength for many structural applications.

Alloy 6061 finds widespread use in manufacturing, appearing in parts from truck frames and bicycle frames to structural supports. The material gains moderate strength through precipitation hardening while keeping solid corrosion resistance and reasonable weldability. When welded with ER4943, the silicon and magnesium from both the base alloy and the filler blend in the weld deposit to provide strong resistance to hot cracking, even in joints with limited movement.

The heat-affected zone experiences softening from the dissolution of strengthening precipitates during welding, but thoughtful joint planning takes this local strength drop into account, ensuring the overall assembly performs as needed.

Applications for 6061 cover a broad range of industries. In transportation, makers rely on it for components where balancing strength and weight matters. Marine builders value its ability to hold up in freshwater and certain saltwater settings. General fabrication shops keep 6061 on hand as a flexible choice that handles varied jobs well.

ER4943 pairs reliably with this alloy across these uses when welders apply suitable methods alongside correct material choices. The combination of 6061 and ER4943 supports practical fabrication in demanding environments. The filler's chemistry complements the base material, producing welds that stay sound under thermal and mechanical stresses typical in these fields. This pairing allows builders to achieve durable structures without excessive complication in welding procedures.

Fabricators working with 6061 appreciate the alloy's machinability and formability alongside its weld performance. These traits make it a go-to option for prototypes as well as production runs. ER4943 enhances this versatility by delivering crack-resistant joints that maintain the alloy's overall benefits.

In summary, alloy 6061 paired with ER4943 offers a dependable route for many structural and functional applications, combining material strengths with welding practicality.

Alloy 6063 dominates the architectural extrusion market, forming window frames, door frames, railings, and decorative trim throughout buildings. The material extrudes easily into complex shapes while providing adequate strength for these applications. With reduced strength relative to 6061, the 6063 alloy is not well-suited for substantial structural loads, though its favorable finishing properties and corrosion resistance make it appropriate for architectural applications.

ER4943 welds 6063 successfully, creating joints that accept anodizing and other finishing treatments, though color matching between weld and base metal requires consideration.

Alloy 6082 in European Specifications

Under European standards, alloy 6082 stands out as a higher-strength option within the 6xxx series. It uses refined element amounts to provide better mechanical properties while keeping the heat-treatable characteristics shared by the group. This combination makes it suitable for structural applications that require increased strength, such as bridge components, crane structures, and transportation frames.

ER4943 pairs with 6082 following the same guidelines as other alloys in the 6xxx family. The silicon and magnesium levels in both the filler and base material create welding conditions that favor crack-free joints. The filler helps manage solidification in a way that maintains weld integrity even in restrained setups common to structural work.

Fabricators working with 6082 appreciate its balance of strength and workability. The alloy responds well to standard welding practices when matched with ER4943, producing joints that hold up under load without special precautions beyond good technique and joint preparation. This reliability supports efficient production in projects where weight reduction and durability matter.

In practice, 6082's composition allows it to achieve useful properties after heat treatment, and welding with ER4943 preserves enough of these traits in the joint area. The filler compensates for changes in the heat-affected zone, delivering welds that meet design expectations for strength and resistance to defects.

Overall, the combination of 6082 and ER4943 offers a practical route for building strong aluminum structures in demanding European applications.

Additional Variants in the 6xxx Series

Other alloys in the 6xxx family address particular needs. Alloy 6005 stands out for its ease of forming into detailed profiles. 6351 brings added strength for pipe and tube in structural roles. 6101 focuses on electrical uses, balancing conductivity with sufficient mechanical performance. All these variants pair well with ER4943 because of their shared compositional foundation and similar responses during welding.

Heat-Affected Zone Considerations for 6xxx Alloys

The heat-affected zone forms in all 6xxx materials, no matter the filler used. The area next to the weld reaches temperatures that dissolve the strengthening precipitates built during heat treatment. Without the precise cooling required for proper re-precipitation, this zone softens and shows lower strength than the untouched base metal. The softened band usually spans several millimeters from the fusion boundary.

Joint planning must factor in this local strength reduction. Designers often add material thickness or reinforcement along load paths to compensate. This approach ensures the overall assembly maintains required performance despite the temporary loss of hardening in the heat-affected region.

Fabricators familiar with 6xxx behavior adjust welding parameters to limit the extent and impact of softening. Lower heat input and controlled travel speed help reduce the zone size, preserving more of the original properties. While post-weld treatments can sometimes recover some strength, many applications rely on as-welded conditions, making careful initial planning important.

ER4943 complements these considerations by producing sound fusion zones that integrate smoothly with the softened adjacent areas. The filler's crack resistance prevents defects that could worsen the strength loss in the heat-affected zone, supporting reliable joints in heat-treatable alloys across varied uses.

| 6xxx Alloy | Typical Applications | Relative Strength | ER4943 Compatibility | Special Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6061 | Structural, automotive, marine | Moderate–High | Very Good | Versatile general purpose |

| 6063 | Architectural extrusions | Moderate | Very Good | Finishing appearance critical |

| 6082 | European structural standard | High | Very Good | Enhanced strength properties |

| 6005 | Complex extrusions | Moderate | Very Good | Excellent formability |

| 6351 | Pipe and tube structures | Moderate–High | Very Good | Pressure vessel applications |

Can ER4943 Join 5xxx Series Aluminum Alloys?

The 5xxx series gains strength from magnesium additions without heat treatment, creating non-heat-treatable alloys that maintain properties more consistently across welded joints than 6xxx materials. Magnesium content varies considerably across the series, ranging from relatively low concentrations to quite high percentages that dramatically affect strength and weldability. This variation creates situations where ER4943 proves suitable for some 5xxx materials while others demand different filler metals.

Lower-magnesium 5xxx alloys, such as 5052, have moderate magnesium levels that make their chemistry work well with ER4943. This material finds use in general fabrication, automotive parts, and marine structures where medium strength is enough. When welded using ER4943, dilution brings silicon from the filler into the weld while magnesium comes mainly from the base, producing a weld metal chemistry close to that seen in 6xxx series joints. The result is welds that resist cracking and offer suitable strength for a wide range of practical applications.

Higher-Magnesium Variants Like 5083, 5086, and 5456

Higher-magnesium alloys such as 5083, 5086, and 5456 bring greater strength thanks to their magnesium levels, but this also makes them more prone to hot cracking. ER4943 can join these materials technically, yet high-magnesium fillers usually match base strength better and avoid the strength gap that can build stress points. Marine structural work especially needs this close strength match, which ER4943 may not fully supply.

Cases where ER4943 fits 5xxx materials include repair welds prioritizing crack control over peak strength, dissimilar joints linking 5xxx to 6xxx where ER4943 acts as a balanced middle ground, and lower-stress parts where the strength difference stays acceptable. Fabricators should assess each job separately instead of using fixed rules.

Marine settings add factors beyond strength matching. Corrosion resistance matters greatly with saltwater contact. The 5xxx series handles corrosion well, but weld metal makeup influences lasting durability. ER4943's silicon changes weld corrosion traits compared to high-magnesium fillers, possibly affecting lifespan in harsh conditions.

Structural uses needing even strength across joints generally prefer matching fillers over ER4943 for high-magnesium 5xxx work. Codes, design specs, and calculations often expect strength levels ER4943 welds may not reach. Reviewing these needs before choosing materials avoids later fixes.

Working with 3xxx Series Alloys and ER4943

Manganese-bearing 3xxx series alloys serve applications where moderate strength, good formability, and adequate corrosion resistance meet requirements without heat treatment complexity. Common materials like 3003 and 3004 appear in cooking utensils, heat exchangers, storage tanks, roofing, and general sheet metal fabrication. The relatively simple composition and non-heat-treatable nature make these materials among the easiest aluminum alloys to weld successfully.

The 3xxx series alloys are compatible with a broad range of aluminum filler metals, providing fabricators with flexible options and minimal compatibility issues. ER4943 performs reliably on these base materials, often producing joints that surpass the base metal strength thanks to its silicon and magnesium additions. This broad acceptance lets shops keep fewer filler types in stock for various jobs, streamlining inventory and easing training needs.

Industrial uses for 3xxx materials cover chemical tanks, food handling gear, building trim, and general sheet work where aluminum's corrosion handling and reasonable strength meet requirements. Welders run into 3xxx alloys frequently in repair or upkeep tasks where exact identification can be tricky. The tolerant nature of these alloys lowers risks when the precise makeup is unclear.

Cost considerations often prompt fabricators to choose 3xxx materials over higher-strength alloys when substantial mechanical properties are not necessary. These alloys carry a lower price tag compared to heat-treatable varieties and do not suffer strength loss from welding heat due to their non-heat-treatable nature. Projects watching expenses closely appreciate the reliable performance and favorable cost balance that 3xxx alloys provide.

Joint appearance and surface finishing generally come out cleanly when using Aluminum Welding Wire ER4943 on 3xxx materials. The similar characteristics between weld and base metal produce tidy results in exposed areas. Anodizing reveals a slight color variation caused by silicon, though the shift remains less noticeable than with fillers containing more silicon.

Pure Aluminum and 1xxx Series Compatibility

The 1xxx series consists of commercially pure aluminum with very few alloying elements. These materials are chosen for uses that rely on properties alloy additions would reduce: electrical conductivity, thermal conductivity, and corrosion resistance in certain chemical settings. Applications include electrical conductors, chemical handling equipment, and decorative parts where purity is key.

Welding pure aluminum brings its own set of challenges compared to alloyed types. The high thermal conductivity draws heat away quickly from the weld area, calling for more heat input to achieve proper fusion. The low inherent strength means joints depend more on thicker sections than on material toughness for load support. Porosity risk rises due to hydrogen behavior differences between molten and solid states.

Filler choice for 1xxx series hinges on the job's priorities. When electrical or thermal conductivity is critical, ER4943's silicon addition lowers these traits noticeably. For conductivity-focused work, pure aluminum fillers are often used, even though they offer less strength and higher crack tendency. The balance between weld soundness and conductivity needs careful thought.

ER4943 can work for 1xxx materials in structural joints where conductivity isn't a concern, repairs on less critical parts, or assemblies where silicon won't affect performance. Chemical equipment sometimes accepts ER4943 welds if the environment handles silicon in the weld zone. Each case calls for separate review rather than broad rules.

Other fillers for pure aluminum include specialized types aimed at high-purity needs. These accept some crack risk to preserve conductivity and chemical fit. Shops dealing regularly with 1xxx series typically keep several filler options to cover different project demands.

Why 2xxx and 7xxx Series Require Different Approaches

High-strength aluminum alloys in the 2xxx and 7xxx series serve applications where mechanical demands exceed what other alloys can supply. Structures in aerospace, defense equipment, and specialized industrial parts depend on these materials for their enhanced properties. The copper in 2xxx alloys and zinc in 7xxx provide this strength but also introduce significant welding difficulties that make ER4943 unsuitable.

Copper-bearing 2xxx series materials show strong hot cracking tendencies during welding. Copper forms low-melting compounds at grain boundaries that stay liquid after the surrounding aluminum solidifies, creating fragile films that tear under cooling stresses. Even moderate copper levels cause issues, rendering standard fillers like ER4943 ineffective. The cracking risk is so high that many 2xxx alloys are viewed as difficult or impractical for conventional fusion welding.

The zinc-bearing 7xxx series encounters comparable challenges. Elevated zinc content increases cracking susceptibility and can produce porosity as zinc vaporizes during heating. The exceptional strength of these alloys in treated states means the heat-affected zone softens noticeably, often dropping joint strength below acceptable levels for load-bearing uses. Engineers in aerospace typically avoid fusion welding 7xxx alloys when possible, opting for mechanical joining instead.

Specialized fillers do exist for cases needing fusion welding of 2xxx or 7xxx materials. These are designed to minimize cracking while providing significant strength. Nevertheless, even with appropriate fillers, welding these alloys demands careful preheating, precise heat control, and specific sequencing. Success remains lower than with more weldable series.

kunliwelding advises that fabricators working with 2xxx or 7xxx materials recognize them as outside ER4943's range. Using ER4943 on these alloys leads to cracked welds regardless of skill or technique. The chemical mismatch cannot be fixed through procedural changes, making accurate material identification essential before starting.

Dissimilar Alloy Combinations with Aluminum Welding Wire ER4943

Practical fabrication and repair frequently involve joining different aluminum alloys in the same structure. Cost optimization often restricts high-performance alloys to high-stress regions, while using more economical alloys in less demanding zones. Specific requirements may demand particular alloys for enhanced corrosion resistance, easier forming, or other characteristics. Repair work commonly requires welding new material onto existing parts made from another alloy series.

In numerous dissimilar joints, ER4943 filler metal serves as a viable option, particularly when one base alloy is from the 6xxx series or comparable low-alloy types. Its chemistry accommodates dilution from both materials, producing welds with satisfactory resistance to hot cracking. Including 2xxx series or high-zinc 7xxx alloys in the joint, however, significantly raises cracking susceptibility and usually requires different fillers or alternative joining methods.

Engineers and welders consider the specific alloy combination, expected dilution effects, and service conditions to decide if ER4943 is acceptable or if another filler or process is more reliable. Test welds on representative samples confirm suitability before proceeding to production parts.

Joining 6xxx series heat-treatable alloys to 5xxx series non-heat-treatable materials represents a common dissimilar combination. Aluminum Welding Wire ER4943 serves this application reasonably well by providing crack resistance while creating weld metal with properties intermediate between the two base materials.

The silicon from ER4943 combines with magnesium from both base metals, producing chemistry that avoids the cracking tendencies of pure magnesium fillers while providing better strength than pure silicon options.

Heat-treatable to non-heat-treatable joints create situations where one side of the weld softens while the other maintains consistent properties. The heat-treatable side develops a softened heat-affected zone while the non-heat-treatable side maintains strength closer to base metal levels. Joint design must account for this property gradient, often by placing critical loads primarily on the non-heat-treatable side or by increasing section thickness on the heat-treatable side.

Galvanic corrosion becomes a concern when dissimilar alloys contact each other in the presence of electrolyte. Different alloy compositions create different electrochemical potentials, and when connected electrically while immersed in conductive fluid, current flows from anodic to cathodic material. The anodic material corrodes accelerated while the cathodic material remains protected. Aluminum alloys typically remain in close proximity within the galvanic series, reducing this effect, though significant combinations can cause issues.

Service environment strongly influences acceptable dissimilar combinations. Dry indoor environments tolerate material pairings that would fail rapidly in marine saltwater exposure. Chemical process equipment demands consideration of how different alloys respond to specific chemicals at process temperatures. Fabricators must evaluate the complete service picture when selecting materials and filler metals for dissimilar joints.

| Base Metal 1 | Base Metal 2 | ER4943 Suitability | Primary Consideration | Alternative Approach |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6061 | 5052 | Good | Strength matching acceptable | Use as specified |

| 6063 | 3003 | Good | Weld stronger than either base | Use as specified |

| 6061 | 5083 | Fair | Strength differential significant | Consider high-Mg filler |

| 6082 | 5086 | Fair | Marine applications need review | Evaluate environment |

| 6063 | 5052 | Good | General fabrication suitable | Use as specified |

Successful joining of dissimilar materials relies heavily on thoughtful joint configuration. Positioning the weld or bond in regions experiencing lower stress levels minimizes the consequences of mismatched properties such as yield strength, modulus, or coefficient of thermal expansion. Increasing material thickness around the joint supplies more cross-section to support loads through potentially compromised areas. Incorporating reinforcement plates, doublers, or similar elements facilitates a smoother load transfer across the interface, thereby enhancing joint performance and durability.

Cast Aluminum Alloys and Application of ER4943 Filler

Cast aluminum alloys exhibit distinct chemical compositions, microstructural features, and property profiles when compared to their wrought counterparts. The solidification process inherent to casting often yields larger grain sizes and can introduce porosity, characteristics typically absent in materials that have been extruded, rolled, or forged. Welding operations on aluminum castings are commonly carried out for repairing casting defects, joining cast parts to wrought sections, or assembling multiple castings into larger structures.

Because cast alloys exhibit different thermal characteristics and solidification patterns compared to wrought materials, specific welding methods and filler metals are required. ER4943 filler metal sees broad use in welding aluminum castings because of its strong chemical match with typical cast alloy compositions. This match results in welds that offer consistent integrity, appropriate mechanical strength, and good protection against hot cracking during solidification.

The main alloys suited to ER4943 are those that already contain silicon for better casting fluidity and mold filling. The base metal's existing silicon level complements the filler's composition, so the additional silicon introduced during welding causes minimal upset to the weld pool chemistry. This balance supports clean solidification with reduced cracking risk.

Alloy 356, along with frequent variants like A356 and related grades such as 357, remains a favored choice for aluminum castings in automotive structures, load-bearing components, and industrial equipment. The alloy employs controlled silicon additions to ensure effective melt flow for intricate molds and includes magnesium to enable precipitation hardening. These characteristics provide good castability, functional strength in the as-cast condition, and notable property improvements through solution treatment and aging.

In welding operations involving these alloys, ER4943 filler wire is commonly recommended, consistently producing welds with adequate strength and integrity for demanding service conditions.

The primary difficulty comes from porosity originating in the original casting solidification, which can transfer into the weld metal and form gas voids. Operators manage this successfully through reduced travel speeds, precise arc adjustments, and strict control of heat input to prevent the formation and trapping of gas pockets.

Porosity Challenges in Welding Cast Aluminum

Porosity remains the principal challenge when welding aluminum castings. Dissolved gases in the melt become trapped during cooling and solidification, producing scattered internal voids throughout the material. Remelting these areas during welding liberates the trapped gas into the weld pool, where it can remain as porosity in the final bead. These voids compromise mechanical properties and may allow leakage in components designed to hold pressure.

Prior to welding, thorough inspection using visual methods or dye penetrant reveals zones of excessive porosity. Mechanically removing surface porosity by grinding or gouging before starting the weld greatly reduces the chance of defects appearing in the finished joint.

Key Practices for Repair Welding

Obtaining sound repair welds on aluminum castings requires meticulous surface preparation and careful control during welding. Cast components commonly carry residual mold release agents, core materials, cutting fluids from machining, or contaminants collected in service. When these substances are present during welding, they volatilize, burn, or react with the arc, producing additional porosity, oxide inclusions, or areas of lack of fusion.

Standard preparation starts with thorough solvent degreasing to dissolve and remove oils and organic films. Next, aggressive mechanical cleaning—typically using stainless steel wire brushes, grinding wheels, or abrasive blasting—removes the persistent oxide film and any embedded foreign matter. This sequence ensures the base metal is clean and receptive, greatly improving the quality and reliability of the resulting repair weld.

In cases of heavy contamination, chemical etching or pickling may be required to expose clean base metal, providing a sound foundation for the repair weld.

Impact of Temper Condition on Welding Behavior

The temper designation assigned to an aluminum component indicates the specific combination of thermal and mechanical processing it has undergone, which in turn governs its strength, ductility, and response to welding. The same base alloy in different tempers can show substantial differences in crack sensitivity, heat input requirements, and final joint performance. Accounting for the existing temper is essential for developing reliable welding procedures and choosing suitable filler metals.

The fully annealed condition, designated by the "O" temper, produces reduced strength but increased ductility. In heat-treatable alloys, this state dissolves the strengthening precipitates formed during aging. In non-heat-treatable alloys, annealing eliminates work hardening from previous deformation. Parts in O temper are generally the easiest to weld, displaying low risk of hot cracking and good tolerance for variations in welding parameters.

Solution heat-treated condition, designated W, represents an unstable intermediate state where alloying elements remain dissolved but natural aging begins at room temperature. Materials in W temper prove quite weldable, similar to annealed material, but the base metal properties change over time as natural aging progresses. Fabricators rarely encounter materials in W temper except immediately after solution heat treatment.

Artificially aged tempers including T4, T6, and variants represent heat-treatable materials processed to develop strengthening precipitates. These conditions provide the high strength that makes heat-treatable alloys valuable but create challenges during welding. The heat-affected zone loses strength as precipitates dissolve, creating the soft zone adjacent to welds. The base metal in T6 condition may show increased crack susceptibility compared to softer tempers due to reduced ductility.

Strain-hardened tempers designated with H numbers indicate non-heat-treatable materials strengthened through cold working. The degree of strain hardening affects weldability somewhat, with heavily cold-worked materials showing slightly increased cracking tendencies compared to annealed conditions. However, the effect remains far less dramatic than temper influences in heat-treatable alloys.

Temper condition influences filler choice primarily through its effect on crack susceptibility. Materials in highly hardened conditions benefit from crack-resistant fillers like ER4943 more than materials in soft conditions. The higher restraint and lower ductility in hardened tempers create conditions favorable for cracking, making filler metal selection more critical.

How should dissimilar alloy combinations be handled with ER4943?

Dissimilar welding raises the complexity because the fusion zone inherits a mixed chemistry that can produce unexpected phases, altered corrosion resistance, and changes in mechanical performance.

Common pairings—such as a 6xxx alloy joined to a 5xxx or to a 3xxx—require a deliberate strategy:

- Balance strength: Design joint geometry and specify weld size so that the as-welded strength is compatible with adjacent base metal allowables.

- Manage galvanic potential: Consider sacrificial protections or isolation when dissimilar alloys create electrochemical couples in corrosive environments.

- Control dilution: Use welding procedures that limit unnecessary melting of the higher-alloyed component; lower dilution preserves desirable base-metal characteristics.

- Adjust filler choice: ER4943 can act as a compromise filler in many 6xxx-to-3xxx or 6xxx-to-5xxx combinations, but for critical joints choose fillers matched to the more corrosion- or strength-critical member.

| Dissimilar Pair | Typical Concern | ER4943 Use Guidance |

|---|---|---|

| 6xxx to 5xxx | Magnesium difference and corrosion | ER4943 acceptable with design allowances; consider corrosion protection |

| 6xxx to 3xxx | Strength mismatch | ER4943 often suitable; expect ductile fusion zone |

| Heat-treatable to non-heat-treatable | Loss of precipitation strengthening | Accept as-welded strength reduction; avoid relying on post-weld heat treatment to restore full base metal strength |

| Wrought to cast | Porosity and silicon differences | Pre-clean, use adapted procedures; ER4943 can be used for many repairs |

The 6xxx series is the primary application territory for ER4943 — why is that the case?

The 6xxx group combines magnesium and silicon to produce precipitation-hardening behavior that delivers a useful balance of strength and extrudability. Many structural and architectural sections are formed from these alloys because they offer good formability and moderate strength with reasonable corrosion resistance. ER4943 is commonly used with this series because its magnesium-silicon balance yields weld metal that, after expected dilution, aligns with the solidification and service requirements of many 6xxx base alloys.

6061 and 6063 exhibit contrasting responses to welding that must be understood. 6061 tends to offer higher base strength but shows greater sensitivity to heat-affected zone softening when precipitation-hardened. When joined with ER4943, designers should expect as-welded joint strength to fall below peak-temper base metal strength, and account for that in allowable stress calculations. 6063, often used in extrusions where surface finish matters, accepts welds with more favorable appearance characteristics but has lower inherent strength; ER4943 produces welds that can be dressed and finished to meet appearance needs while preserving corrosion performance.

European alloys such as 6082, with their higher-strength chemistry, can be welded with ER4943 for applications where crack resistance is a priority, but joint design and heat input must be managed to avoid excessive softening. Other members of the 6xxx family (6005, 6351, 6101) behave similarly but require attention to heat input and joint detail because differences in alloying and temper can change weldability margins.

| Base Alloy | Typical Use | Compatibility Notes with ER4943 | Expected Joint Behavior |

|---|---|---|---|

| 6061 (T-temper) | Structural frames, fittings | Common pairing; dilution reduces peak strength | HAZ softening; reduced as-welded strength |

| 6063 | Architectural extrusions | Good surface appearance after dressing | Lower strength; good finishing outcomes |

| 6082 | Higher-strength structural sections | Acceptable when heat input controlled | Higher sensitivity to HAZ effects |

| 6005 / 6351 / 6101 | Extrusions, electrical sections | Generally compatible with process adjustments | Variable HAZ softening; monitor distortion |

Can ER4943 join 5xxx series alloys?

The 5xxx series is magnesium-dominant, providing strong corrosion resistance in marine environments and good weldability in many tempers. However, the magnesium content varies widely across the series, and elevated magnesium levels—particularly above certain thresholds—can increase the occurrence of solidification cracking unless appropriate filler chemistry and welding procedures are selected.

ER4943 can be appropriate for some 5xxx materials in situations where the base metal's magnesium content is moderate and the service load and environment do not require substantial strength. For high-magnesium alloys and those used in highly corrosive environments, specialized high-magnesium filler metals are sometimes required to match electrochemical behavior and mechanical expectations.

Considerations for common 5xxx alloys:

- 5052: Moderate magnesium content; good general weldability; ER4943 often provides acceptable joints for non-critical structural uses where corrosion resistance remains satisfactory.

- 5083 / 5086: Higher-strength, marine-grade alloys with elevated magnesium; caution is required—ER4943 may be used for repairs or non-critical joints, but high-magnesium fillers are preferred for heavy structural applications.

- 5454: Designed for welding; ER4943 may be acceptable depending on design allowables and service conditions. Corrosion resistance and strength matching must be evaluated together for marine and structural uses. Galvanic potential differences with mating materials and local service exposure should guide filler choice.

Why do 3xxx series alloys accept a variety of fillers?

3xxx series alloys rely primarily on manganese for strength, which is not strongly affected by thermal cycles from welding. That makes alloys like 3003 and 3004 relatively forgiving with respect to filler selection: they do not depend on precipitation hardening, so dilution of alloying elements typically has less detrimental effect on post-weld properties. ER4943 performs well on these materials in many fabrication contexts, providing acceptable mechanical performance and good surface quality when finished.

Common uses include tankage, sheet goods, and architectural components where formability and surface finish are priorities. For such applications, the cost-effective pairing of 3xxx base metals with ER4943 often represents a good balance between joint performance and fabrication economy.

When is ER4943 acceptable for pure aluminum and 1xxx series materials?

The 1xxx series is essentially commercially pure aluminum, prized for thermal and electrical conductivity and corrosion resistance. Adding silicon through filler metal lowers conductivity and slightly alters corrosion behavior, so filler choice must balance mechanical requirements with functional conductivity.

ER4943 can be used on 1xxx series materials when structural or repair needs outweigh strict conductivity or when the design allows for modest conductivity reduction in welded zones. Alternative filler metals that preserve conductivity more closely are typically used where electrical performance is critical. For chemical process or architectural applications where conductivity is less important, ER4943 provides sound weldability and reasonable corrosion performance.

Why do 2xxx and 7xxx series alloys require specialized approaches?

Alloys in the copper-bearing 2xxx series and the zinc-bearing 7xxx series achieve high strength through age-hardening mechanisms but are also highly crack-sensitive under conventional fusion-welding conditions. The presence of copper or high zinc levels leads to solidification paths that favor the formation of low-melting eutectics and segregation, increasing the risk of hot cracking.

As a result, ER4943 is generally inadequate for direct fusion welding of these alloys when high strength must be retained. Specialized filler alloys, controlled preheat and post-weld treatments, or alternative joining methods (such as friction stir welding or brazing under controlled conditions) are commonly employed for these alloys in demanding structural applications. Aerospace and other high-integrity fields impose stringent metallurgical and procedural controls that make filler selection and post-weld processing critical.

Corrosion Resistance in Various Alloy Combinations

Long-term durability of aluminum structures depends heavily on corrosion resistance in service environments. While aluminum generally resists corrosion better than carbon steel, specific alloy combinations and environments create situations where rapid deterioration occurs. Weld metal composition affects corrosion behavior, making filler metal selection important for durability alongside mechanical properties.

The galvanic series orders metals and alloys by electrode potential in seawater. In electrical contact within an electrolyte, the more anodic metal corrodes acceleratedly, while the cathodic one stays protected. Aluminum alloys span a limited range in the series, yet key variations occur: copper-alloyed 2xxx series position more cathodically, and high-magnesium 5xxx series lean more anodic.

Corrosion in Marine Conditions

Marine exposure delivers aggressive corrosion via saltwater electrolyte, plentiful oxygen, and thermal fluctuations. Aluminum protection relies on its quick-forming oxide layer. Seawater chlorides penetrate this barrier, sparking localized corrosion. Performance hinges on alloy family, as 5xxx and 6xxx series resist effectively while 2xxx series succumb more readily.

Industrial Environment Corrosion

Industrial atmospheres often include sulfur compounds, chlorides, or other pollutants that attack aluminum. Certain agents cause intergranular corrosion along grain boundaries, resulting in strength reduction with limited visible surface indicators. Weld zones, due to microstructural changes and element segregation, are especially prone to this type of attack.

Stress Corrosion Cracking

Stress corrosion cracking develops when tensile stress and a corrosive environment combine to drive crack growth at loads far below normal strength limits. Susceptibility varies greatly by alloy family: high-strength 7xxx series are highly prone, whereas 6xxx series typically resist well. Welding-induced residual stresses can initiate this failure mode even without external loading.

Corrosion Behavior of ER4943 Welds

Weld metal deposited with ER4943 filler wire generally exhibits solid corrosion resistance in many service environments. The silicon content has little negative impact on corrosion properties, and the absence of copper avoids a common weakness. For marine or industrial applications, the full assembly—base alloys, weld deposit, and any contacting dissimilar metals—should be assessed to confirm suitable long-term corrosion performance.

Coatings and surface treatments provide extra corrosion protection in demanding environments. Anodizing builds a thicker oxide layer for enhanced resistance and color possibilities. Paint or powder coatings act as barriers to corrosive elements. Conversion coatings aid paint bonding while offering some direct protection. The appropriate choice balances appearance requirements, cost factors, and the intensity of the anticipated exposure.

Color Matching and Anodizing Considerations

Anodizing is routinely applied to architectural and decorative aluminum components to boost corrosion resistance and create targeted visual finishes. The process uses electrochemical action to develop a porous oxide layer that accepts dyes before being sealed. Silicon content in the alloy impacts oxide growth and dye absorption, frequently producing color variations between the base material and welds of different composition.

ER4943 filler wire's higher silicon level results in weld areas that anodize darker than standard 6xxx series parent alloys. The elevated silicon affects oxide formation and color uptake, creating visible contrast. This disparity appears particularly evident in clear anodize or lighter tints. Richer colors like bronze or black substantially hide the difference between weld deposit and adjacent base metal.

Welded architectural structures needing uniform finish call for measures to control color differences. Positioning welds out of sight removes the concern altogether. Grinding and polishing can smooth the weld bead and unify surfaces, although this requires additional labor and removes some material. Permitting minor color variation as normal for welded aluminum is feasible when aesthetic standards allow flexibility.

Pre-anodizing surface preparation plays a major role in the final appearance. Sandblasting creates textured matte surfaces that lessen apparent color mismatches, while chemical brightening produces glossy finishes that emphasize differences between weld and base metal. The preparation method must take into account the compositional variations present in the welded assembly.

Mechanical finishing methods—grinding, sanding, and polishing—reliably merge weld zones with surrounding areas. These techniques work well on smaller parts or shorter welds but demand more effort on large assemblies with lengthy joints. Material removal must be carefully managed to avoid thinning sections below required thicknesses. Accurate control preserves necessary dimensions while achieving the desired visual consistency.

Industry-Specific Alloy Selection Guidelines

Industries develop distinct material preferences and guidelines shaped by their operational needs and historical performance data. Understanding these sector-specific conventions helps fabricators in selecting suitable base alloys and filler metals for intended applications. While underlying compatibility fundamentals hold steady, established industry habits steer routine choices.

Automotive Industry Practices

Automotive builders primarily choose 6xxx series alloys for structural frames, body sheets, and chassis sections. These materials provide a practical combination of reasonable strength, enhanced formability, and adequate corrosion protection, enabling efficient and economical production. ER4943 filler metal proves effective for automotive welding, yielding reliable, crack-free joints on the prevalent heat-treatable alloys in modern vehicles. The push for lighter weight through expanded aluminum adoption has heightened the importance of dependable welding techniques.

Marine Industry Practices

Marine construction traditionally relies on 5xxx series non-heat-treatable alloys for their substantial strength and effective saltwater corrosion resistance. Still, 6xxx series alloys see service in select marine roles, often on smaller boats or secondary components. Marine welding protocols treat corrosion resistance as critically as structural strength. ER4943 performs suitably on 6xxx parts and lower-magnesium 5xxx alloys, but higher-magnesium 5xxx constructions generally call for fillers matched to their magnesium content.

Architectural Applications

Architectural designs prioritize aesthetic excellence alongside structural soundness. Facades, curtain walls, window frames, and decorative accents make full use of aluminum's corrosion resistance, lightweight characteristics, and extensive finishing possibilities. Alloy 6063 is a common selection for extruded architectural profiles, valued for its favorable surface finish qualities and adequate strength properties. ER4943 ensures dependable welding results in architectural work, provided color consistency is carefully handled on anodized surfaces where welds are visible.

Transportation applications including rail cars, trailers, and specialized vehicles use various aluminum alloys depending on specific component requirements. Structural frames may use higher-strength 6xxx or 5xxx materials, while panels and enclosures often employ lighter-gauge 3xxx or 5xxx sheet. The mixed materials in typical transportation structures create situations where dissimilar welding becomes necessary. ER4943's broad compatibility makes it useful across many of these combinations.

Pressure vessel and tank construction demands materials and welding procedures that maintain leak-tight integrity throughout service life. Non-heat-treatable 5xxx series alloys dominate pressure vessel construction due to their consistent strength across welded joints. Storage tanks for chemicals or cryogenic fluids require particular attention to material compatibility with contents. ER4943 suitability for pressure vessels depends on specific base materials and service conditions.

Food and Beverage Industry Applications

Aluminum is commonly used in food and beverage equipment due to its effective corrosion resistance and non-toxic nature. The 3xxx series alloys are common in applications requiring moderate strength, while 5xxx series materials are selected when greater strength is needed. Sanitary welding standards require smooth, crevice-free welds that facilitate complete cleaning and prevent contamination. ER4943 filler metal produces joints that satisfy food industry hygiene demands when proper welding technique achieves clean profiles with minimal reinforcement and no undercut.

Troubleshooting Incompatible Alloy Combinations

Despite careful material selection, situations arise where base metal and filler metal combinations produce unsatisfactory results. Recognizing incompatibility symptoms helps identify problems and guide corrective actions. Common indicators include cracking, porosity, inadequate strength, corrosion problems, or appearance issues that appear despite apparently correct procedures.

Troubleshooting Weld Imperfections

Cracking patterns provide clues to underlying causes and remedies. Hot cracks, which occur during solidification, typically appear as straight lines along the weld centerline or in the crater. They signal a broad solidification temperature range or poor fluidity in the weld metal. Changing to a more resistant filler such as ER4943 often resolves hot cracking when a less appropriate filler was used initially. Persistent cracking even with ER4943 usually points to base metal issues, such as copper or zinc content that promotes unavoidable cracking sensitivity.

Consistent porosity despite adequate shielding gas and clean surfaces indicates problems in the base material. Castings with internal porosity release trapped gas into the weld pool. Zinc-bearing base metals produce porosity as the zinc vaporizes under welding heat. High-magnesium alloys can also generate porosity in certain situations. Parameter adjustments may lessen the issue, but severe porosity often reveals incompatible material pairings that demand alternative fillers or methods.

Strength shortfalls identified in testing or field failures warrant review of filler choice. Welds markedly weaker than anticipated can result from using ER4943 on high-magnesium 5xxx alloys, where strength recovery requires fillers with matching magnesium levels. ER4943's moderate strength aligns well with 6xxx series alloys but may fall short for applications needing the full capability of 5xxx base metals.

Corrosion issues arising in service can sometimes stem from galvanic differences between weld deposit and base metal or between dissimilar base metals joined by welding. Localized attack near welds highlights electrochemical mismatches. Switching fillers or applying protective coatings can mitigate these problems.

Alternatives When ER4943 Is Unsuitable

When ER4943 does not perform adequately, other fillers offer solutions: higher-silicon types for better crack resistance at the expense of some strength, high-magnesium fillers to match 5xxx properties, or specialized compositions tailored to difficult alloys. Unexpected base metal compositions occasionally explain poor results. Positive material identification using spectroscopy or similar techniques verifies actual alloy content when composition is uncertain.

Practical Selection Process for Real-World Applications

Fabricators must weigh multiple factors when choosing filler metals for particular jobs. A systematic evaluation process ensures key aspects are considered instead of depending only on habit or prior experience. Although practical knowledge informs decisions, structured assessment helps avoid missing critical compatibility needs that surface only during welding or later in service.

The starting point is reliable identification of the base materials. Examining mill reports, checking stamped identifications, or performing compositional checks establishes the exact alloy and temper. Guessing material type—especially with secondary or salvaged stock—courts trouble. Confirming identity at the outset avoids incompatibility revelations after major welding effort.

Clarifying service conditions defines the performance targets that choices must hit. Structural loads, corrosive exposures, operating temperatures, appearance standards, and applicable codes all guide suitable selections. Prioritizing these demands separates critical requirements from less vital aspects.

Choosing an appropriate filler metal usually involves managing trade-offs between different performance features. A filler designed for substantial joint strength may carry increased susceptibility to solidification cracking. Another selected specifically for ideal color harmony in anodized finishes could provide somewhat reduced strength properties. Understanding and accepting these built-in compromises helps ensure selections that focus on the application's main priorities rather than trying to achieve top performance in every single category.

Seeking Expert Guidance

Bringing in welding engineers or metallurgists supplies helpful viewpoints on unusual alloy pairings, challenging operating conditions, or materials not routinely encountered. Their theoretical expertise and diverse practical background nicely round out everyday shop experience. Operations without on-staff specialists can obtain comparable assistance from outside consultants or through technical services offered by suppliers.

Cost and Performance Balance

Cost assessments call for a practical review of what the project actually requires. Requesting expensive fillers or involved welding procedures when suitable, less costly alternatives would perform adequately drives up expenses without delivering real improvement. Conversely, cutting corners by weakening essential characteristics often results in service problems whose repair costs greatly exceed the money initially saved. Sorting out which qualities are truly required from those that are simply nice to have promotes sensible and effective budgeting.

Supply and lead-time factors affect choices on schedule-driven projects. Unusual alloys or tempers can involve lengthy procurement delays. Knowing which alternatives remain acceptable preserves timelines while upholding required properties.

Future Trends in Aluminum Alloy Development

Ongoing advancements in materials science regularly deliver new aluminum alloys tailored to meet evolving performance demands. These innovations provide greater design possibilities while introducing fresh considerations for welding and joining. Staying informed on changing alloy compositions enables fabricators to embrace advantageous developments and effectively manage associated fabrication challenges.

Commercially introduced alloys generally target shortcomings in established series, seeking to combine traits once viewed as mutually exclusive—such as higher strength alongside retained ductility or enhanced corrosion protection without reduced formability. These purpose-built materials increase engineering flexibility yet necessitate verification of compatibility with common fillers like ER4943 or the creation of specialized welding consumables.

Sustainability efforts increasingly highlight aluminum's recyclability, though expanded use of recycled feedstock introduces compositional variation from mixed scrap sources. Such fluctuation can influence welding reliability and often demands procedures able to handle wider alloy tolerances.

Wire-fed additive manufacturing processes create additional applications for welding consumables. Layer-by-layer deposition subjects material to repeated thermal excursions that severely test cracking resistance. ER4943's inherent low-cracking behavior may suit these methods, though the unique thermal history could necessitate further procedural adjustments.

Standards and codes evolve to include new alloys, modern test protocols, and refined qualification criteria as knowledge accumulates. Relevant committees regularly update documents to incorporate improved practices and resolve issues identified in service. Monitoring relevant revisions maintains compliance and enables adoption of improved techniques.

Core aluminum welding compatibility principles remain constant despite changing alloy introductions. Mastering these fundamentals allows systematic evaluation of new materials rather than exhaustive trial for each development. Cultivating strong grasp of compatibility fundamentals equips fabricators to navigate current alloys and future arrivals confidently.

The recognition that ER4943 succeeds with 6xxx series through balanced silicon-magnesium chemistry applies equally to assessing any emerging composition via its elemental content. This timeless, principle-based foundation endures beyond specific alloy lists, supporting sustained capability as demands for lighter, stronger, and more durable aluminum structures continue to grow.

Successful aluminum fabrication depends on carefully matching base metal properties, operating environment demands, and filler metal performance, rather than defaulting to familiar or readily available options. ER4943 aluminum welding wire proves particularly valuable when used with compatible alloy groups, especially those where silicon and magnesium levels promote stable solidification, consistent mechanical properties, and dependable corrosion resistance in the welded joint.

Understanding the situations where ER4943 performs best—and recognizing when other fillers or techniques are required—allows fabricators and designers to tackle standard production runs and challenging assemblies with increased assurance. This thoughtful, material-centered approach contributes to durable long-term service, more efficient manufacturing processes, and better preparedness for ongoing developments in aluminum alloys and their applications.

NEXT:How Joint Design Selection Influences ER4943 Performance?

Related Products

-

View More

View More

5154 Aluminum Alloy Welding Wire

-

View More

View More

ER4043 Silicon Aluminum Welding Wire

-

View More

View More

ER4047 Aluminum Mig Welding Wire

-

View More

View More

ER5154 Al-Mg Alloy Wire

-

View More

View More

ER5087 Magnesium Aluminum Welding Wire

-

View More

View More

Aluminum Welding Wire ER5183

-

View More

View More

Aluminum Welding Wire ER5356

-

View More

View More

ER5554 Aluminum Welding Wire

-

View More

View More

ER5556 Aluminum Welding Wire

-

View More

View More

ER1100 Aluminum Welding Wire

-

View More

View More

ER5754 Aluminum Welding Wire

-

View More

View More

ER2319 Aluminum Welding Wire